- Home

-

Day tours

- Day tours

-

Marsa alam tours

-

Hurghada tours

-

El Quseir Tours

-

Makadi bay

-

Cairo Tours

- Cairo Tours

- Top Things in Cairo

- Siwa tours from Cairo

- Cairo Culture Tours

- Alexandria trips from Cairo

- Nile Cruises From Cairo

- Night Dinner Cruises in Cairo

- Sound and Light show Excursion

- Fayoum trips from Cairo

- Luxor Tours From Cairo

- white desert trips from Cairo

- Al Minya tours from Cairo

- Cairo Travel Packages

- Cairo Desert and Safari tours

- Aswan tours From Cairo

- Cairo Taxi Transfers

-

Luxor Tours

-

Portghalib tours

-

Sharm el Sheikh

-

El Gouna Tours

-

Aswan Tours

-

Sahl Hasheesh Tours

-

Soma Bay tours

- Safaga Tours

-

Airport Transfer

-

Tour Packages

- Tour Packages

-

Egypt Travel Packages

- Egypt Travel Packages

- Egypt Itinerary 4 Days

- Egypt Itinerary 5 Days

- Egypt Itinerary 6 Days

- Egypt itineraries 7 Days

- Egypt itineraries 8 Days

- Egypt Itinerary 9 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 10 Days

- Egypt Itinerary 11 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 12 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 13 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 14 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 15 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 16 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 17 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 18 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 19 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 20 Days

- Egypt Itineraries 21 Days

- Top Egypt Vacation Packages

- Egypt Cruises Packages

- Egypt Christmas Holidays

- Hurghada Holiday Packages

- Marsa Alam holidays packages

- Marsa Alam tour Packages

- Egypt Walking Holidays

-

Shore Excursions

- Egypt Nile Cruises

-

Egypt Attractions

- Egypt Attractions

-

Top Attractions In Luxor

-

Top attractions in Bahariya

-

Top Attractions In Fayoum

-

Top Attractions In Siwa

-

Top attractions in Sakkara

-

Top Attractions In Giza

-

Top Attractions In Aswan

-

Top Attractions In Alexandria

-

Top Attractions In Cairo

-

Attractions in Damietta

-

Top Attractions In Hurghada

-

Top Attractions in El Quseir

- Top attractions in Marsa Alam

- Top attractions in Al Minya

- Top attractions in El Gouna

- Top attractions in Sharm

- Contact us

-

Egypt Travel Guide

- Egypt Travel Guide

- Egypt tours Faq

- Egypt Itinerary 7 Days

- Best Tours in Marsa Alam

- Egypt Itinerary 8 Days

- Travel to siwa from Cairo

- Plan your trip to Egypt

- Is Egypt Safe to Visit

- Egypt Itinerary Planner

- The Best Winter Destinations

- Egypt Tour Packages guide

- The best Nile Cruises in Egypt

- Tips For visiting the Pyramid

- Foods You Need to Eat In Egypt

- The 10 Best Marsa Alam Tours

- Payment Policy

- Covid-19

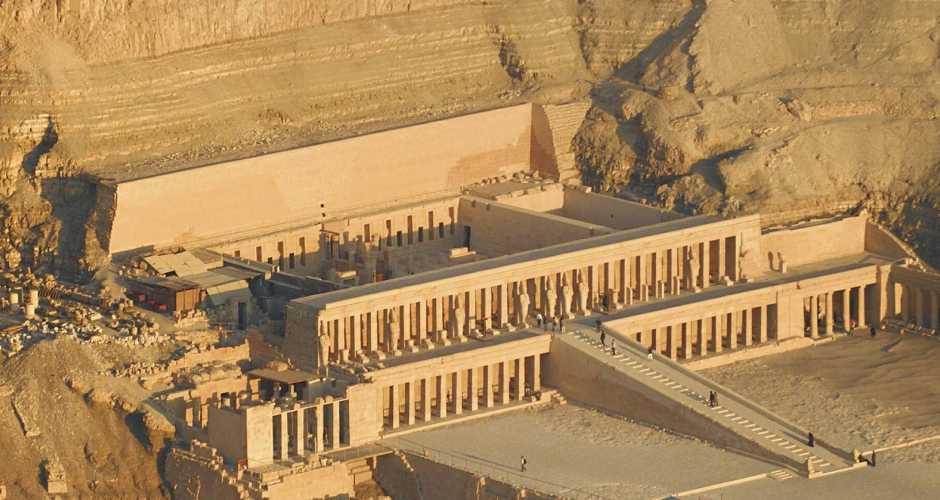

THE MORTUARY TEMPLE OF HATSHEPSUT AT DEIR EL-BAHRI

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri

Important Theban religious and funerary site on the west bank of the Nile, opposite Luxor, comprising temples and tombs dating from the early Middle Kingdom to the Ptolemaic period. The site consists of a deep bay in the Nebhepetra (Mentuhotep II)(2055-2004 BC), cliffs containing the remains of the temples of Hatshepsut (1473-1458 BC) and Thutmose III (1479-1425 bc), as well as private tombs contemporary with each of these pharaohs. The temple of Hatshepsut is the best-preserved of the three, consisting of three collonaded terraces imitating the architectural style of Mentuhotep's much earlier funerary complex immediately to the south of it. As well as incorporating chapels to Hathor, Anubis and Amun, The name Deir el-Bahri means ‘Northern Monastery’, indicating that the site was once used by Christian monks. Prior to the coming of Christianity, however, the site in the Valley of the Kings was a complex of mortuary temples and tombs built by the ancient Egyptians. One of the most famous of the mortuary temples at Deir el-Bahri in the Temple of Hatshepsut.

Hatshepsut is arguably one of the most formidable women in ancient Egypt. After the death of her husband, Thutmose II, Hatshepsut served as co-regent to her nephew and stepson, the infant Thutmose III, who would eventually become the 6 the pharaoh of the 18 the Dynasty. The roughly 22-year reign of Hatshepsut is generally regarded as one of Egypt’s most prosperous, and major accomplishments were achieved by this extraordinary pharaoh, including the construction of her mortuary temple in Deir el-Bahri. Thanks to its design and decorations, the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir El-Bahri is one of the most distinctive temples in all of Egypt. It was built of limestone, not sandstone like most of the other funerary temples of the New Kingdom period.

Senimut

It is thought that Senimut, the genius architect who built this Temple, found inspiration in his design by the plan of the neighbouring mortuary, Temple of the 12th Dynasty King, Neb-Hept-Re. The Temple was built to commemorate the achievements of the great Queen Hatshepsut (18th Dynasty), and as a funerary Temple for her, as well as a sanctuary of the god, Amon Ra.

In the 7th century AD, it was named after a Coptic monastery in the area, known as the “Northern Monastery”. Today it's known as the Temple of Deir El-Bahri, which means in Arabic, the “Temple of the Northern Monastery”. There is a theory suggesting that the Temple, in the Early Christian Period, was used as a Coptic monastery. This unique temple describes the conflict between Hatshepsut, and her nephew and son in law, Tuthmosis III, since many of her statues were destroyed, and the followers of Tuthmosis III damaged most of her Cartouches, after the mysterious death of the queen. The Temple consists of three imposing terraces. The two lower ones would have once been full of trees. On the southern end of the 1st colonnade, there are some scenes, among them the famous scene of the transportation of Hatshepsut’s two obelisks. On the north side of the colonnade, there is a scene that represents the Queen offering four calves to Amon Ra.

Descriptions

The 2nd terrace is now accessed by a ramp; originally it would have had stairs. The famous Punt relief is engraved on the southern side of the 2nd colonnade. The journey to Punt (now called Somalia) was the first pictorial documentation of a trade expedition that was recorded, and discovered, in ancient Egypt; until now. The scenes depicted in great detail, the maritime expedition that Queen Hatshepsut sent, via the Red Sea, to Punt, just before the 9th year of her reign (1482 B.C) This famous expedition was headed by her high official, Pa-easy, and lasted for 3 years. His mission was to exchange Egyptian merchandise for the products of Punt, especially gold, incense and tropical trees.

To the south, there is the shrine of the Goddess Hathor. The court that leads to this chapel has columns, where Hathor, who is shown with a woman’s face and cow’s ears, is carrying a sistrum (a musical tool), yet on the walls, she is depicted as a cow. In this part of the Temple, King Tuthmosis III erased the Queen’s names.

On the northern side of the 2nd colonnade, there is a scene depicting the divine birth of Hatshepsut. The Queen claimed that she was the divine daughter of Amon Ra to legitimize her rule. Beyond the colonnade to the North is the chapel of Anubis, god of mummification and the keeper of the necropolis. The 3rd terrace is also accessed by a ramp. It consists of two rows of columns, the front ones taking the Osiris form (a mummy form); unfortunately, Tuthmosis III damaged them. The columns at the rear, sadly, have all been destroyed; also by Tuthmosis III. He obviously bore a real grudge against the former queen!

The Deir el-Bahri Mummy Cache

Deir el-Bahri is also the site of a mummy cache, a collection of pharaohs' preserved bodies, retrieved from their tombs during the 21st dynasty of the New Kingdom. Looting of pharaonic tombs had become rampant, and in response, the priests Pinudjem I [1070-1037 BC] and Pinudjem II [990-969 BC] opened the ancient tombs, identified the mummies as best they could, rewrapped them and placed them in one of (at least) two caches: Queen Inhapi's tomb in Deir el-Bahri (room 320) and the Tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35).

The Deir el-Bahri cache included mummies of the 18th and 19th dynasty leaders Amenhotep I; Tuthmose I, II, and III; Ramses I and II, and the patriarch Seti I. The KV35 cache included Tuthmose IV, Ramses IV, V, and VI, Amenophis III and Merneptah. In both caches there were unidentified mummies, some of which were set in unmarked coffins or stacked in corridors; and some of the rulers, such as Tutankhamun, were not found by the priests.

The mummy cache in Deir el-Bahri was rediscovered in 1875 and excavated over the next few years by French archaeologist Gaston Maspero, director of the Egyptian Antiquities Service. The mummies were removed to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where Maspero unwrapped them. The KV35 cache was discovered by Victor Loret in 1898; these mummies were also moved to Cairo and unwrapped.

A successful trade mission to a foreign land, however, was not enough to portray Hatshepsut as a good pharaoh or indeed as a pharaoh at all. As a woman, Hatshepsut was defying the norm by being pharaoh, a position reserved by males only. Thus, she had to legitimize her claim to the Egyptian throne. This resulted in the elaborate birth story found on the mortuary temple’s ‘Birth colonnade’. According to the story on the colonnade, Hatshepsut was not a mere mortal but had divine parentage, as the god Amun himself, taking the form of the pharaoh Thutmose I, went to Hatshepsut’s mother, Ahmose, and impregnated her with his divine breath. Amun then reveals his true self to Ahmose and foretells that Hatshepsut will rule over Egypt. Khnum, the creator of the bodies of human children, is then instructed to form Hatshepsut’s body and ka (life force). Ahmose is then led by Khnum and Heqet to the birthing chamber and with the help of Meskhenet, Hatshepsut is born. Finally, Hatshepsut is shown suckled by Hathor, whilst her birth is recorded by Seshat. With so many gods involved in her birth, Hatshepsut was almost certain to have cemented her claim as pharaoh. As a point of interest, the same birth story can also be found in Karnak. The colonnade, which leads to the sanctuary of the Temple, has also been severely damaged. This sanctuary consists of two small chapels. In the Ptolemaic period, a third chapel was added to the sanctuary, which was also decorated with various scenes, the most remarkable being the ones representing Amenhotep, son of Habo (18th Dynasty) who, like Imhotep from the 3rd Dynasty, was another genius architect from Ancient Egypt.